epe era Barbero. El padre de Pepe fue barbero. También lo había sido su

abuelo Pepe, y su bisabuelo Pepe, y su tatarabuelo Pepe, y su tataratatarabuelo

Pepe, y su tatarataratatarabuelo Pepe, y su tataratataratataratatarabuelo Pepe,

y su tataratataratataratataratatarabuelo Pepe.

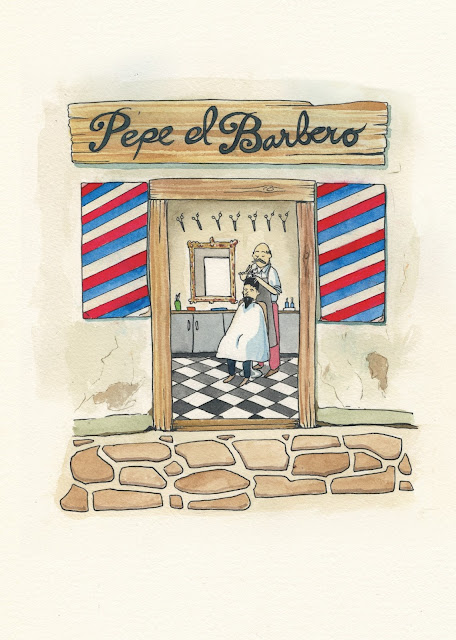

Los Fígaro, ese era su nombre de familia, ejercieron todos su profesión en

la misma barbería, en una estrecha calle del casco antiguo de la ciudad. Con las

mismas rayas azules, rojas y blancas custodiando la puerta. Los clientes de

Pepe se sentaban en la misma silla de cuero envejecido en la que se habían

sentado los clientes de su tataratataratataratataratatarabuelo Pepe. El pelo

recién cortado caía sobre las mismas baldosas de piedra blanca y negra, desgastada

por nueve generaciones de barridos. En los cansados espejos, enmarcados en

vieja madera, se habían dibujado todo tipo de barbas, bigotes y peinados;

reflejo de las modas de cada época. En la pared colgaban las ocho tijeras de

los ocho Pepes anteriores. La barbería se llamaba, como no podía ser de otra

manera, Barbería Pepe.

Pepe nunca cuestionó su oficio. Igual que nunca había cuestionado sus

ojos marrones, su nariz afilada, su boca pequeña custodiada por pequeños

dientes, los pelos de su bigote a los que nunca sometía a la navaja, su baja

estatura, sus dedos delgados y largos perfectos para coger las tijeras, o su

pelo negro y rizado que con el tiempo fue abandonándolo y cubriéndose de

ceniza. Por supuesto tampoco cuestionó nunca su nombre. Desde que tuvo uso de

razón supo cuál era su lugar en el mundo.

Desde muy niño pasaba todo el tiempo que podía en la barbería,

prácticamente se podría decir que se crió en ella. Con tres años se encargaba

de barrer, actividad que hacía de forma silenciosa, rápida y eficaz. Daba la

extraña sensación de que los pelos nunca tocaban el suelo que se mantenía

impoluto.

Con seis años le dejaron usar la brocha de afeitar, y comenzar a lavar el

pelo. Al ser tan pequeño tenía que subirse a un taburete, desde el que trabajaba

con sus diminutas manos con sorprendente seguridad. Transmitía una paz y una

serenidad que dejaba a los clientes en un profundo estado de placentera calma.

En su noveno cumpleaños su padre le regaló unas tijeras y una navaja. Pepe

jamás olvidaría la ilusión que sintió al abrir el estuche de terciopelo azul,

forrado por dentro de seda roja. La hoja de la navaja, de brillante y afilado

acero, se plegaba escondida en un mango traslúcido de cuerno natural. Las

tijeras eran iguales a todas las que colgaban en la pared, con las mismas

iniciales grabadas: P.F. Las dos largas hojas cruzadas unidas por un tornillo le

recordaron a una boca cerrada, que espera abrirse para pronunciar la primera

palabra. De ellas nacían dos anillos. Uno un poco más grande, para el pulgar. Otro

un poco más pequeño para el dedo anular, con una pequeña cola que servía de

apoyo al dedo meñique.

Esa noche, después de cerrar, estando los dos en la barbería, Pepe padre se

sentó en la butaca y Pepe hijo entendió que había llegado su momento. Sin

mediar palabra sacó de un cajón una sábana blanca y la abrió de un solo

movimiento que envolvió al padre anudándose en su cuello. Llenó un pequeño

cuenco de agua templada. Colocó el taburete junto a la silla. Puso un poco de

crema en la barbilla, humedeció la brocha, y con abocetados movimientos

circulares las suaves cerdas de tejón extendieron la crema por su rostro hasta

convertirla en abundante espuma. Abrió el estuche y sacó la navaja. Con un

sutil golpe de dedo se abrió por primera vez, mostrándose la cuchilla

brillante, y apoyándose el mango en su palma. No le tembló la mano al dar su primera

pasada, ni en la segunda, ni en la tercera… Recorrió el rostro con trazos

precisos y seguros, consiguiendo un afeitado tan apurado que si bien realizó

una segunda pasada fue más por ceremonia que por necesidad. Limpió la navaja,

la secó, y la guardó en el estuche. Cogió las tijeras por primera vez. Sus

dedos se deslizaron naturalmente en los anillos, llevaban toda la vida

esperando a hacerlo. Al abrirlas el sonido le pareció música. Comenzó a cortar

el cabello. Las tijeras se abrían y cerraban al compás que el pequeño Pepe

marcaba con el pie. Pepe padre, que llevaba años entre murmullos de tijeras que

se abrían y cerraban, nunca había escuchado nada igual. La tenue música llenaba

el silencio de la barbería vacía. Y lo más curioso de todo era, que a pesar de

estar seguro de no haberla oído nunca, le era familiar, como si fuera una

cadencia escondida desde siempre en su ser, esperando a brotar desde la

esencia. Al mirarse en el espejo se vio rejuvenecido y apuesto. Tuvo la

sensación de re-encontrase consigo mismo, de verse por primera vez reconociendo

lo que siempre había sido.

Pasaron los años. Pepe se hizo adolescente, joven y adulto; siempre con las

tijeras en la mano. De cada cliente que se sentaba en su silla manaba una

música diferente. Todos tenían su propio compás, marcado por el pie de Pepe

golpeando el suelo. Todos tenían su propia melodía entonada por las tijeras.

Todos salían de la barbería rejuvenecidos, viéndose apuestos, e impulsados por

una fuerza interior que les mostraba el camino para sentirse realizados.

Pepe padre murió, y sus tijeras ocuparon su lugar en la pared, junto a las

otras siete marcadas por las letras P.F.

Cliente a cliente la música se fue transformando en forma. En un principio sutilmente,

pero cada vez con un presencia más obvia. Al herrero le dejó la cabeza con

forma de yunque. El carpintero parecía tener un enjambre de clavos en la cabeza.

Los rizos de un filósofo se asemejaban a nubes cúmulos. Y cuando un abogado

aburrido de las leyes salió de la barbería con su pelo transformado en

almazara, dejó el bufete, se compró un pequeño olivar, y dedicó el resto de sus

días a hacer aceite.

Su fama se extendió rápidamente. Por el barrio, la ciudad, la provincia, el

país entero, Europa y el mundo. Fue portada de las más prestigiosas revistas. Grandes

corporaciones llamaron a su puerta haciéndole ofertas mareantes en las que los

ceros se sucedían de tres en tres. Pero Pepe, hijo de Pepe, nieto de Pepe, bisnieto

de Pepe, tataranieto de Pepe, tataratataranieto de Pepe,

tataratataratataranieto de Pepe, tataratataratataratataranieto de Pepe y

tataratataratataratataratataranieto de Pepe, nunca quiso dejar la barbería en

la que los Fígaro habían ejercido su profesión desde tantas generaciones atrás.

Se formaban colas tan largas a la puerta de la barbería que llegaban a dar

tres vueltas a la manzana. Comenzó a trabajar cada vez más rápido. La música no

variaba. La melodía era la misma. El pulso del ritmo se multiplicaba. X2. X4.

X16. X256. X65536. X4294967296.

Cuanto más rápido trabajaba más clientes tenía. Ya no daba tiempo a barrer

el pelo del suelo. Esperaban al final del día y lo absorbían con una aspiradora

industrial.

Los clientes eran guiados entre el pelo ajeno hasta el sillón. Los

movimientos de Pepe eran tan veloces que mantenían un espacio en torno suyo en el

que se podía respirar.

Las colas crecieron hasta dar nueve vueltas a la manzana.

En los espejos ya no se dibujaba nada. No había luz que reflejar.

No se veían las paredes. Ni las tijeras de los ocho Pepes anteriores.

La aspiradora industrial fue insuficiente. Trajeron un enorme camión

cisterna para succionarlo. Casi no cabía en la estrecha calle.

Llegó a haber tanto pelo que cuando se abría la puerta se escapaba.

Pepe tenía que trabajar más y más rápido. Era la única forma de mantener ese

espacio en el que se podía respirar.

Cada vez más densidad de pelo.

Cada vez más difícil de sostener.

Cada vez más presión.

Trabaja día y noche.

Se toma un respiro.

Un escaso segundo.

En lugar de aire sus pulmones se llenan de pelo.

Muere.

El escaparate de la barbería revienta. La gran masa de pelo se esparce

cubriendo el cielo de la ciudad, tapando el sol durante nueve días.

En una ciudad vecina, un pelo se mete por la rendija de una ventana,

posándose grácilmente sobre un plato de sopa. Una elegante mujer, con un

vestido de flores, y collar y pendientes de perlas, atrapa el caliente caldo

con una cuchara sopera de plata, en un movimiento circular que comienza

alejándose de ella, para tras trazar un arco morir en sus labios pintados de

carmín. Sorbe la sopa silenciosamente. Repara en algo extraño en su paladar.

Hasta tres veces saca la lengua pegándola a los labios. Por fin nota algo en la

punta de la lengua. Formando con su dedo pulgar y su dedo índice una pinza

atrapa el pelo. Estira de él extrayéndolo de su boca. Lo mira confusa. Es

largo, rizado y pelirrojo. En su casa son todos morenos.

“Someone who

believes in infinite growth is either a madman or an economist.” – David Attenborough

A.M.B.

Ilustrado

por Mark Morgan Dunstan

Noviembre de 2015